The Mirror Trap

When Silence Was the Sharpest Reply

My transition period lasted just two weeks. That was all the time my superior allowed before handing me the reins to a diplomatic post in Washington, D.C. In those 14 days, I had to steer the helm alone—managing official briefings, securing housing, and figuring out how to survive in a foreign capital. I bought a car, moved into a small place, and tried to memorize the exits on the Beltway. I got lost often, but I got the job done.

Then, six months into the post, I received quiet word from a colleague: my big boss was already pulling strings to send me back to Taipei. No explanation. No confrontation. Just orchestration behind the scenes.

So I made a move of my own.

If the embassy had become a stage, maybe the university could offer something more neutral. I applied to three programs at Johns Hopkins’ D.C. campus and ended up sitting across from three professors at once, undergoing a crossfire interview. When it was over, they stepped outside to discuss—and returned to tell me I’d been accepted. Not into a master’s program, but endorsed directly for doctoral study.

It was flattering. But I didn’t need another degree. I needed air.

I consulted a contact at the Pentagon—a pious Catholic, quiet but well-placed—and he suggested Georgetown. I applied to their English graduate program, but was referred to Liberal Studies instead. He even wrote the recommendation for me personally. The program was rigorous, interdisciplinary, and good for the mind and soul.

But I still needed something tactical—something that would give me a niche in the job market, not just peace of mind. So I enrolled in a Public Relations certificate program at George Washington University. Their educational center was close to my office, and the class schedule fit between briefings and embassy duties.

Before long, I was a full-time diplomat and a part-time student—drafting cables by day, reading strategy cases by night. What a busy, meaningful life I had in D.C.

At Georgetown, we spoke in theories.

At GW, the classroom was a miniature office—filled with students from every corner of the PR world: nonprofit consultants, magazine editors, federal contractors. Everyone was already performing. No one had to say it out loud. The goal wasn’t to learn how to communicate—it was to prove you already could.

The older woman who always arrived late turned out to be a radio host in Baltimore. One day, she slid into class twenty minutes late and announced, “It’s impossible to drive from Baltimore to downtown D.C. without a delay.”

The instructor didn’t flinch.

Didn’t nod.

Didn’t even look up.

That silence wasn’t indifference. It was dominance.

Another classmate—a young, long-haired man—would prop his legs on the table long after class began. The instructor approached and asked where he worked.

“CIA,” the student answered.

“How do you know I’m not from CIA?” the instructor replied.

We all laughed nervously. But we understood. This wasn’t a lecture hall. This was a soft theater of control.

Still, the instructor’s reach was real. We took a field trip to Washingtonian Magazine and met with the chief editor. We spoke with an embedded war reporter just back from Iraq. Another guest had a Pulitzer.

This wasn’t academic. This was grooming.

I still remember our first in-class exercise: a paired role-play interview, followed by a written news feature.

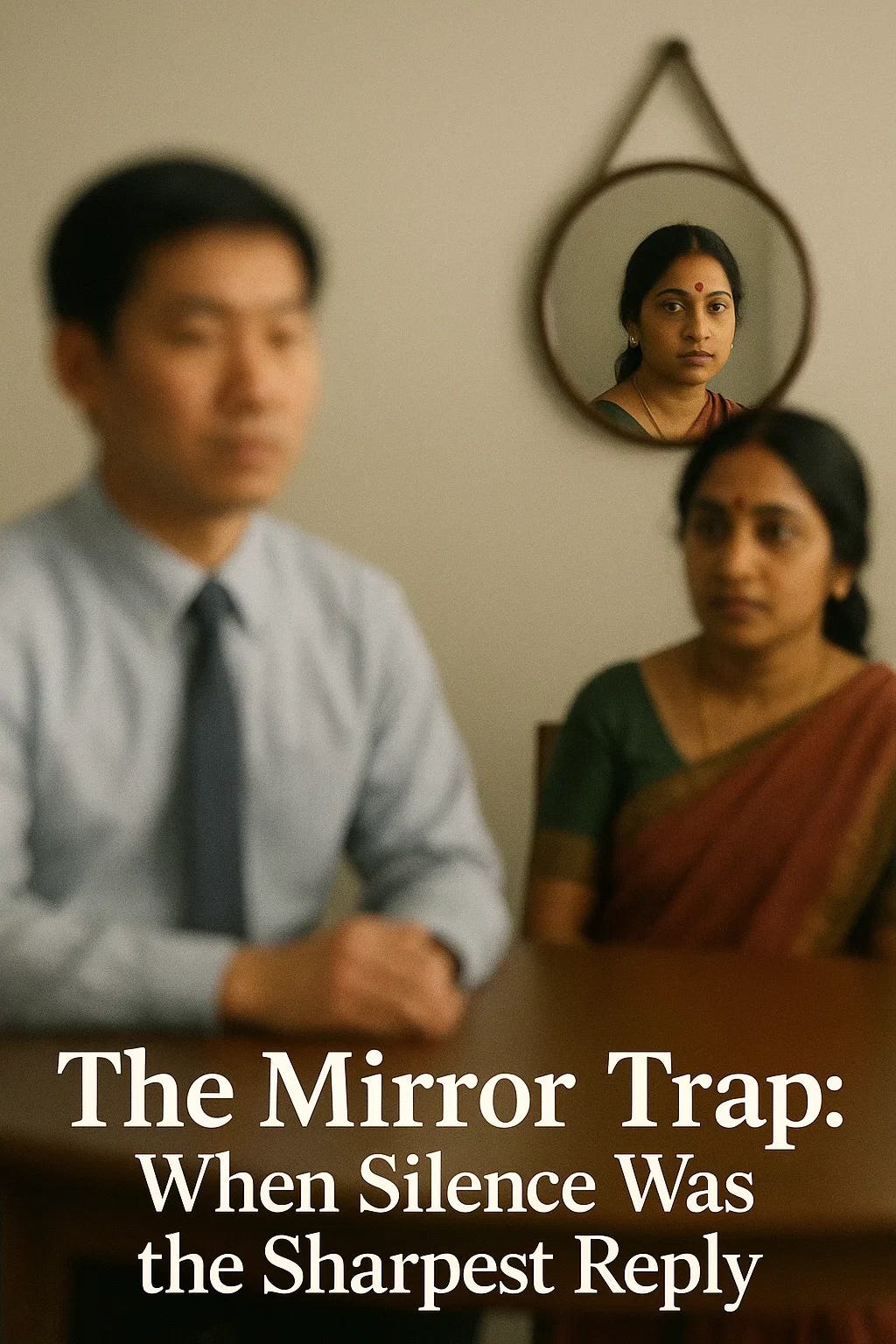

I was paired with a young woman wearing traditional Indian attire—a long robe-like dress, a red bindi on her forehead. Her presence was quiet but deliberate. When she spoke, her English was smooth, neutral—just like any American office worker.

No accent, no hesitation.

Second-generation, I thought. Raised here, trained here. She reminded me of students I’d seen from Taiwan or China—heritage on display, voice fully adapted.

When she interviewed me, her tone was relaxed. Her English was clear. It was easy to answer her questions.

But something didn’t sit right.

Some of her questions didn’t follow contextual logic. One would touch on diplomacy; the next would veer into personal credibility or image. They felt rehearsed, not responsive—as if she’d written them before she ever heard my answers.

And then I saw it:

The subtle twitch in her brow.

The way her eyes scanned my face—not for understanding, but for effect.

She wasn’t there to listen.

She was there to frame.

When it was my turn, I played it straight. I asked direct questions, like a real reporter would.

She answered fluently—beautifully, even—but her responses didn’t connect. They floated. Like she was reading a monologue from a different script.

When we finished, we each presented our write-ups to the class.

She went first.

Her summary of our exchange sounded polished—but underneath, it was critical. Not overtly, but the tone was there. The framing was sharp, just cynical enough to imply without accusing.

I didn’t flinch.

And neither did she.

Maybe she thought I hadn’t noticed.

Maybe she mistook my silence for confusion.

Then it was my turn.

I walked the class through my report—just the facts, the questions, her answers. I stayed within the exercise.

Until the end.

I paused. Looked up from my page. Met her eyes for a second.

Then I said:

“But one thing I was curious about is her major in English literature and her love of William Shakespeare…

which has nothing to do with her current job on nuclear armament.”

She froze.

Her eyebrows shot up—two startled caterpillars arched in disbelief.

And from the corner of my eye, I saw it:

The instructor frowned.

Class ended a few moments later.

No one said a word.

And I never saw that Indian lady again.

Postscript

She may have thought silence meant surrender.

But silence is not absence.

It is reservation.

The choice not to play someone else’s game—even when you know the rules better than they do.

In diplomacy, in education, in performance—language is never neutral.

It reveals.

It conceals.

And sometimes, it waits.

Sun Tzu once said, “The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting.”

That day, I didn’t fight.

I let the mirror do the work.